(Sumera Saleem)

With which metaphor the violence of Islami Jamiat-i-Talaba in the field of education can be depicted? It depends on how the lens of observation sets its focus on the activism of violence that channelizes its agenda and tactics. Often leaving the students baffled in the face of meaningless or rather violent activities of IJT repetitious dialogues on the part of the administration in controlling the situation remain in a Sisyphean spiral.

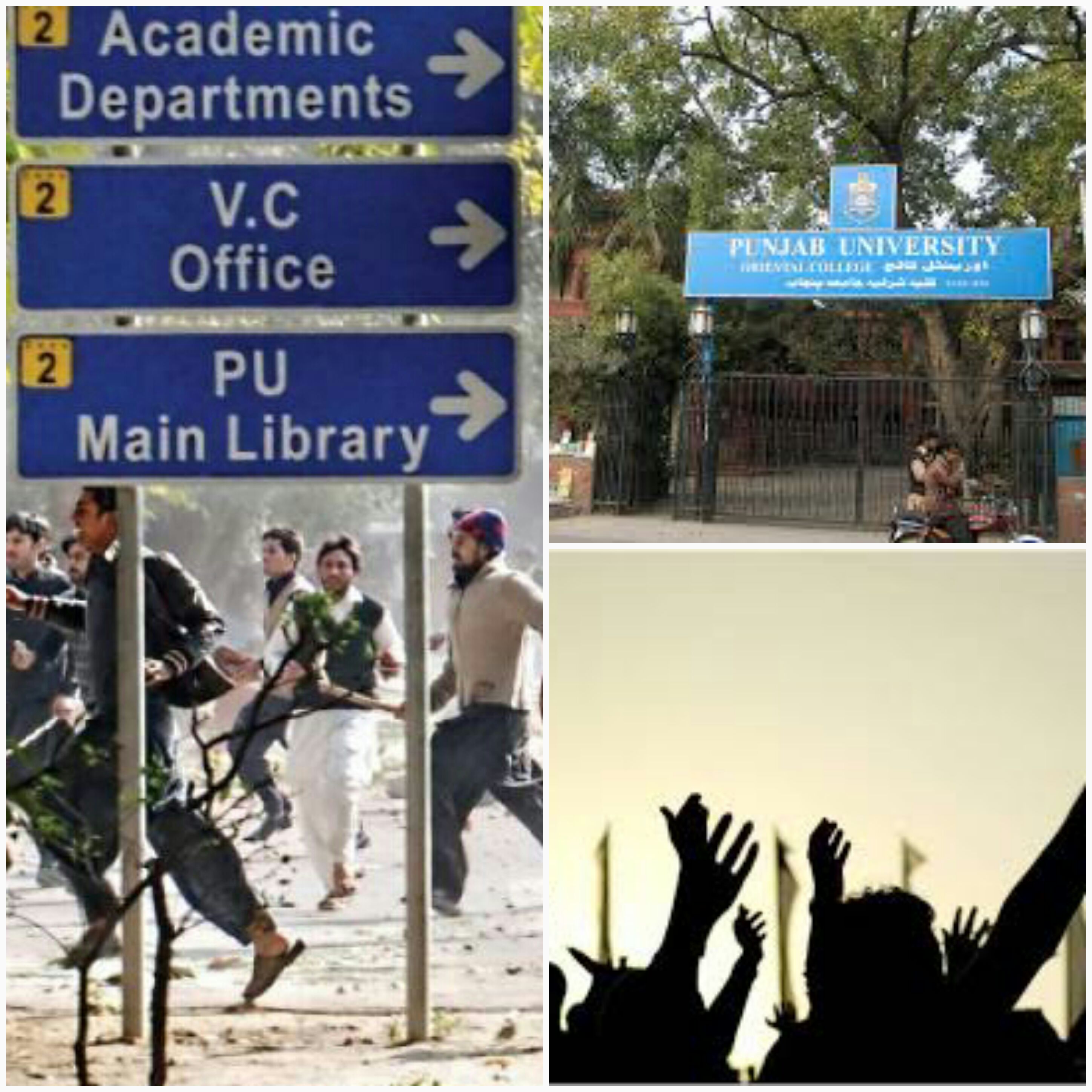

The riots with which the sense of fear permeated in PU suggest all communication for building a peaceful atmosphere has broken down to the level of senselessness before IJT’s irrational and illogical agenda of exerting influence over the students, teachers and administration of the institute.

Absurdism; a term used to characterise the work of a number of European and American dramatists of the 1950s and early 1960s proposes “the human situation is essentially absurd, devoid of purpose”. The Existentialist philosopher, Albert Camus, brings forth this view is in his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942).

Drawing on this idea, the situation made up by IJT in PU is strategically absurd as the activists are blemishing the purpose of education; ‘to think critically’. To define the atmosphere in the university as absurd is to recognise the fundamentally indecipherable nature of violence executed by IJT, and this recognition is frequently associated with feelings of loss, purposelessness, and bewilderment. Students’ bewilderment and anxiousness at the inaction of the management is quite baffling.

The stereotypical mindset, a seminal feature of absurdism, turns up the face of chaos erupted in the form of a clash between Islami Jamiat Talaba (IJT) and Pushtoon Educational Development Movement (PEDM). Dozens of students from various universities on Saturday staged a peaceful protest outside the Lahore Press Club against the clash. However, the question arises “when will the cycle of IJT’s extremism come to a halt? “

Frantic harassment of IJT and the inspections on the part of the administrative committees are working in cyclic movement without reaching an end. The actions taken on the part of the administration range from hollow clichés to irritating inaction. Inaction against the “hooligans” stems from VC Prof. Dr Zafar Mueen Nasar’s withdrawing of orders against IJT activists involved in violence.

Even according to Punjab Education Minister Rana Mashhood Ahmad Khan the government decided “to pick linchpins and register cases against them under the anti-terrorism act”, no significant step was undertaken. As soon as the inquiry committee recommends an action, IJT lines up another incident for it to probe.

Filing of an application with police station or forming of a committee or constituting an inquiry team would not in any way gurantee an end of the game being played by IJT. “The problem is not just “the mindset” of IJT as while speaking at the press conference Dr Zafar said on 18 January. Rather it’s the interminable activities of IJT and inaction of the administration that “needed to be combated.”

Aligning itself with absurdist tradition where words play on ‘contradiction’ IJT has taken a contradictory approach towards raising its voice and ruling over others’ opinion. Shoaibuddin Kakakhel, IJT Pakistan head, recorded a protest against the ban on students’ union which, he demonstrates, speaks of the policy of dictators “in silencing the voice of the educated youth,” His remarks need to be taken seriously regarding the action and thoughts with which IJT is snatching students’ right to carve the ways of critical thinking.

Torturing the students for using social media, following of anti-education and anti-student policies and gruesome attacks by IJT on the students epitomise IJT’s agenda of intolerance, violence and hooliganism. Such contradiction exposes the absurdity of the system meant for future society by IJT.

IJT’s ideology, as Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) Pakistan Chief Sirajul Haq on 16th January 2017 explained, inscribes a utopian worldview anchoring its aims at “creating a society where ways for virtue and good deeds would remain open and committing a sin would become difficult.” Bearing upon the fear of IJT, life for the students particularly living in PU hostels has become “difficult” and in my humble view life is not a ‘sin’. As the eyes are sick of seeing “nothing has been done” hope remains in glow that the immediate and meaningful action on the part of the administration will not lead the students to render futile exertion and toil in rolling their voice up and down against hooliganism of Jamiat activists in a Sisyphean cycle.

Great effort against a terrorist violence absurd movement