The Art of Humor

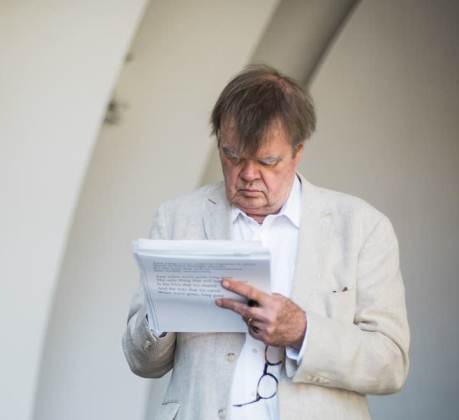

Garrison Keillor , Interviewed by George Plimpton

Garrison Keillor was born in 1942 in Anoka, Minnesota. He attended Anoka High School and the University of Minnesota. In 1969, he began writing for The New Yorker. In 1974, while at work on an article about the Grand Ole Opry, he was inspired to create a live variety show for radio. The result was the award-winning A Prairie Home Companion, an inspired program in which Keillor—invariably appearing on stage in the World Theater in downtown St. Paul in a tuxedo, red suspenders, and jogging sneakers—brought his listeners the latest news from the fictional town of Lake Wobegon. The show was “sponsored” by, among others, Ralph’s Pretty Good Grocery (“if you can’t find it at Ralph’s, you can probably get along without it”). His chronicling of a Midwest culture and its gentle homespun ways (in the tradition of Booth Tarkington and certainly Mark Twain) have resulted in a number of books, among them We Are Still Married, Happy to Be Here, Lake Wobegon Days, WLT: A Radio Romance, Leaving Home, and The Book of Guys. He left The New Yorker at its last administrative change, and at what he perceived to be a shift in its editorial policy; he now contributes regularly to The New York Times and The Atlantic Monthly. In addition to A Prairie Home Companion, Keillor also hosts The Writer’s Almanac, a daily poetry program distributed by Public Radio International.

This interview was conducted on the stage of the YMHA at Ninety-second Street and Lexington Avenue in New York as part of a continuing series arranged between that institution and The Paris Review. The auditorium was packed, the balcony as well, many in the audience with his books—well-thumbed copies of Lake Wobegon Days in particular—which they would get him to autograph afterwards.

Keillor is a large man, very tall, built along the lines of professional football’s tight ends. He has a heavy crop of dark hair, which is distinguished by a forelock clump that reaches almost to his right eyebrow. His is a large and expressive face, which with his dark-rimmed glasses gives him a somewhat solemn and owlish appearance: he never appears to laugh, even at his most hilarious. The pace of his replies is slow and measured, giving one the sense that he has applied a good deal of thought to the question, however uninspired.

The introduction on the stage concluded with a listing of some of the more distinguished literary figures who have been interviewed on the craft of fiction for the Review—a pantheon Keillor was now joining.

INTERVIEWER

The Paris Review interviews on the craft of writing started back in 1953, the first interviewee being E. M. Forster. The interviews have appeared in the magazine, which is a quarterly, ever since. We are extremely glad to welcome Garrison Keillor to the pantheon and to their good company.

GARRISON KEILLOR

I’m glad that sales of my books have dropped to where serious literary journals now take an interest in me.

INTERVIEWER

Well, fortunately, we had to wait a long time for that to happen. Could we start by asking if the process of writing is pleasurable?

KEILLOR

Sometimes, but it doesn’t have to be; you still have to do your work. I write for a radio show that, no matter what, will go on the air Saturday at five o’clock central time. You learn to write toward that deadline, to let the adrenaline pick you up on Friday morning and carry you through, to cook up a monologue about Lake Wobegon and get to the theater on time. That can be pleasurable, but only if the material you write is good. If it’s not, you’re filled with self-loathing. If the material is good and funny, you still loathe yourself, of course, for writing comedy and lighthearted fluff instead of writing serious and loathsome fiction, but . . . What was your question?

INTERVIEWER

No, you were doing fine. During this time from Friday until Saturday a part of your brain must be working on what you are going to put down. What is the genesis of a particular piece? Can you describe what that is like?

KEILLOR

You mean the Lake Wobegon stories? They aim to be truthful, so that’s where they originate, in the search for truth. I told a story a month ago, for Halloween, about the terrible pranks that were played in Lake Wobegon just before I came along that I never got to participate in. Things such as pushing over an outhouse when some sterling citizen was in it, tipping it forwards so it fell on the door and the poor man had to crawl out the hole. I never did this. It existed for me only in my uncle’s stories, but the stories were severely edited. So I had to reconstruct what happened when an outhouse was tipped, how it must have felt to the man inside and what a pleasure it must have been to the tipper.

INTERVIEWER

When does your own imagination take over a story that an uncle told you?

KEILLOR

Well, my uncle was not willing to tell me the whole story, only to acknowledge that he had heard of people doing that sort of thing. He wasn’t willing to put a hand on the outhouse himself. In his version, he was far away at a Bible reading, which diminished the story. I don’t consider it fiction to complete someone else’s story that they for the wrong reasons cut short or revised. Although I never tipped an outhouse over, I could tell about it—any writer could. How many ways are there to tip over an outhouse, after all? And who wouldn’t do it, given the chance to? And you know whose outhouses would be really worth tipping over. And would you tip it over onto its back? No. Of course you’d tip it onto the front.

INTERVIEWER

I would think so.

KEILLOR

Leaving your victim only the one exit, and so it’s uh . . . I don’t consider it fiction, it’s more like working out a theorem. And if you can imagine how to tip over an outhouse, you’re ready to go on and write about homicide.

INTERVIEWER

Well, how about the genesis of something longer? For example, “My North Dakota Railroad Days,” your marvelous story about an imaginary railroad train?

KEILLOR

My father worked on the railroad, for the Railway Mail Service, sorting mail in the mail car, and his run was St. Paul to Jamestown, North Dakota and back. Their trains were very romantic to me as a boy in Minnesota. You could hear the whistles from miles away when I was a teenager. I rode the Burlington Zephyr to Chicago, and the North Coast Limited, and years later I set out to write about a train that was even greater than those trains, a train that those trains were trying to be. The Prairie Queen, which crossed North Dakota, a state in which it was possible to lay straight track for hundreds of miles without hitting anything that couldn’t easily be removed. The passengers stood on the rear of the platform of the parlor car in the trans–Dakota Canal, and trolled for fish, and they played pocket billiards onboard. After I wrote that for The New Yorker, it was republished in North Dakota, in a magazine for railroad old-timers, and it drew some testy letters from old-timers who couldn’t recall any sort of train like that. When people take pure fiction as journalism, there is no greater compliment.

INTERVIEWER

I take it you did not write back to the railroad magazine.

KEILLOR

No. I clipped out those irate letters and framed them.

INTERVIEWER

Being considered a humorist, are you constantly aware that it’s time to come up with something as clever as you’ve just described, or to be comic in some way?

KEILLOR

No, I think that past the age of thirty there is no obligation to be clever at all. Cleverness is a burden after that. You are supposed to settle down and be a good person, raise your children, and be good to your friends, which you may not have been back when you were clever.

INTERVIEWER

So you are not really aware of an audience, as you write, that you have to entertain in some way?

KEILLOR

There is an audience that listens to Prairie Home Companion, and I feel obligated to do something for them, just as you would be obligated to clean your house and make food if you had friends coming over at seven o’clock. They don’t demand that you be clever or profound, only to be in good humor, or lacking that, to be brief.

INTERVIEWER

Do they read The New Yorker?

KEILLOR

The audience for the radio show?

INTERVIEWER

Yes.

KEILLOR

No, I don’t think they do. They never mentioned it if they do. Most people I know used to feel bad that they didn’t have time to read the magazine and now they don’t anymore. Anyway, I don’t write for The New Yorker anymore.

INTERVIEWER

You once wrote about The New Yorker as being an immense literary ocean liner off the coast of Minnesota, so it must have had an enormous impression upon you at one time.

KEILLOR

It’s moved off the coast of Minnesota, and now it is firmly anchored off the coast of Staten Island.

INTERVIEWER

Have you informed them of this?

KEILLOR

Yes. When I heard that Ms. Brown was the new editor, having read magazines she had edited in the past, I decided that twenty-some good years was privilege enough, and I packed up my office into cardboard boxes, loaded them into an elevator, and went away in a cab.

INTERVIEWER

Where will these marvelous pieces of yours now appear?

KEILLOR

I don’t have a magazine. I’ve been de-horsed. So I’m a pedestrian now.

INTERVIEWER

Now, does that mean you are not going to write, or will you continue to write stories that would have been in the old New Yorker?

KEILLOR

No, I am saving them up. And looking for a home, like the boll weevil.

INTERVIEWER

Has Tina Brown of The New Yorker tried to call you on the telephone?

KEILLOR

No, I don’t think so. Has she mentioned anything to you?

INTERVIEWER

I am perfectly willing to be an intermediary if you would like.

KEILLOR

Ms. Brown, God bless her and God help her, is one of those crazy people who do not realize that the Midwest exists. The country is collapsed between two coasts in the minds of these people; the interior terrifies them. They are afraid to go to Cleveland or Chicago, afraid people won’t know who they are, afraid their ATM cards won’t work.

INTERVIEWER

Well, that’s why I would assume that she’d be very anxious to publish your work. The Minnesota correspondent.

KEILLOR

There are no famous people in Minnesota and no good murder trials. Nothing there to interest her.

INTERVIEWER

Well, when you did work at The New Yorker what was the atmosphere like then? I mean about editing in particular?

KEILLOR

It was a wonderful place for a writer. It could be disconcerting, in that editors avoided by word, deed, or nuance ever suggesting what they might like you to write about, for fear of spooking you. I found it weird. But once you got going on something, it was a great place to work. There wasn’t a lot of hanging out at The New Yorker. When you went into your office and closed the door, people didn’t bother you. They had the respect that writers have for each other’s time. When you finished, you would run up to the nineteenth floor and stick it on Chip McGrath’s desk, the managing editor. And you’d walk back to your office, and he would tell you within an hour if they liked it or not. It would go into proof right away if it was a casual or “Talk of the Town” piece, which were what I wrote, and you’d get to see it in galleys that same week. And the next week, you would correct it and a couple days after that it was on a newsstand. So it was a shop that took writing very seriously, and had a great reverence for writers, and it also had the feeling of a country, weekly newspaper, which was where I started to write. When I was fourteen, I wrote for the Anoka Herald. It smelled somewhat like The New Yorker, the ink proofs, the piles of old newspapers, and the people were a little run down at the heels. And you got to see what you’d written right away afterward. That was joyful, to work on a weekly schedule for a magazine that cared about writing.

INTERVIEWER

Did Mr. McGrath ever say, I’m terribly sorry we don’t like this very much? This is not quite up to snuff, or however they would put it?

KEILLOR

Well, when The New Yorker rejected work, they did it in an elaborately polite way, apologizing for their shortsightedness, that undoubtedly it was their fault, but somehow this story fell slightly short of your remarkably high standard. They had a way of rejecting my work that made me feel sorry for them, somehow.

INTERVIEWER

How easily did the “Talk of the Town” pieces come to you?

KEILLOR

I just walked around the city. I think a Midwesterner does not have to walk around New York very long before something springs to mind. If you can’t find something to write about by walking around, then you find it by standing in one place and waiting.

INTERVIEWER

But you have extraordinarily capable equipment to do this—an eye for detail, even a sense of smell.

KEILLOR

I don’t have much equipment at all. I have a very poor sense of smell. I don’t have a great eye for detail. I leave blanks in all of my stories. I leave out all detail, which leaves the reader to fill in something better.

INTERVIEWER

Come on.

KEILLOR

Like Hemingway. Hemingway burned off the underbrush, and his stuff leaps to life.

INTERVIEWER

Well, I was reading a story of yours the other day, in which you go on at great length about creamers and automatic milking systems. Nothing left to the imagination at all.

KEILLOR

Automatic milking systems? In a story of mine?

INTERVIEWER

Yes indeed.

KEILLOR

I didn’t know you read dairy journals.

INTERVIEWER

But you must rely on a lot of catalogues. The Wobegon pieces are marvelously full of detail about what’s in a barbershop, what is here, what is there, what are in the store windows. No?

KEILLOR

No. The Lake Wobegon stories are remarkably empty of detail. They are like twenty-minute haiku, they are absolutely formal and without detail. This is what permits people who grew up in Sandusky, Ohio, or Honolulu, Hawaii, or people who grew up in Staten Island for God’s sake, to imagine that I’m talking about their hometown.

INTERVIEWER

Really? I see very little similarity between here on Ninety-second Street and Wobegon, at least as concerns the milking equipment.

KEILLOR

Well, it depends on whether you’re talking about East Ninety-second or West Ninety-second. No. You see I talk very slowly, especially when I do those Lake Wobegon stories, because as I talk I am thinking about what comes next, if anything. I talk so slowly that I couldn’t possibly put in details or I would never get to the end. I talk in subjects and verbs, and sort of wind around in concentric circles until I get far enough away from the beginning so that I can call it the end, and it ends. I’m passing on a lot of secrets to you right now.

INTERVIEWER

I can hardly wait to try them out, starting with talking slowly. When you do the Wobegon radio pieces, will you then turn them into stories for—not The New Yorker anymore—but for a collection?

KEILLOR

I did that once, for a book called Leaving Home. Those stories were very close to what I did on the air. I had to fix up my grammar, of course. Those stories seemed to work so well without any detail that now I use even less, but they were very close to what was on the air. I did want them to have a little more shape than what they’d had on the air, and I tried to make myself look more literate, goodness knows, than if you simply did a transcript of those stories. But beyond that, no, I didn’t add that much to them. It seemed to have worked so well the first time without any detail that I wouldn’t want to add any to it.

INTERVIEWER

Why is humor such a rare commodity? Why are there so few American humorists?

KEILLOR

Well, I think there are quite a few. How many should there be? How many do we need?

INTERVIEWER

More than there are, I think.

KEILLOR

You think we need more?

INTERVIEWER

Well, I’m thinking really of editors, who pray for something they can put in their magazines that is, not wit necessarily, but humor.

KEILLOR

I don’t know. Humor has to surprise us, otherwise it isn’t funny. It’s a death knell for a writer to be labeled a humorist because then it’s not a surprise anymore. It’s what’s demanded of him. And when you demand humor of people you will never get it. I have been working on editing an anthology of humor, a hellish task, and you wind up beating the bushes for humor, looking for it, demanding it, expecting it, and suddenly nothing looks funny to you anymore now that you are a professional humor anthologist. When you were an innocent reader and they sprang up at you out of the weeds, they made you laugh out loud. S. J. Perelman used to make me laugh out loud on planes. We don’t have more humorists because we don’t need them. And nobody wants to live with one. They’re very hard to live with. I’ve been told that. So the fear of loneliness discourages people from going into the field.

INTERVIEWER

What about rereading E. B. White, who was one of your great idols. White, A. J. Liebling and indeed Perelman you thought were the great titans of the time. Have you dared reread White and Liebling?

KEILLOR

They are all three of them beautiful writers, and you could teach a year of English just using the three of them.

INTERVIEWER

What did you learn from them particularly?

KEILLOR

I tried awfully hard to imitate them, and that helps you to get through a lot of your own dreadful early writing and get into something else. A. J. Liebling, who for years you could only find in used bookstores, now has been very handsomely reissued. My favorites were The Road Back to Paris and The Earl of Louisiana. But everything that he wrote was gorgeous. He was the most elegant American writer ever, very sweet, and a funny man. E. B. White was a master of the educated, democratic prose style. As a teacher he is the equal of Mark Twain. And S. J. Perelman will teach you how to do what E. B. White teaches you not to.

INTERVIEWER

Any of your contemporaries make you laugh out loud?

KEILLOR

Yes, Ian Frazier and Nora Ephron, Veronica Geng, Roy Blount, Calvin Trillin. So does Dave Barry. I think a lot of Dave Barry. Even though all of Dave Barry’s books are entitled Dave Barry. But Blount is the best. He can be literate, uncouth, and soulful all in one sentence.

INTERVIEWER

What is the first mistake that someone trying to write humor almost invariably makes? What goes wrong almost invariably?

KEILLOR

When some people sit down to write humor, they adopt a giddy tone of voice, a whooping or comic warble, so that the reader will know it’s funny. It’s the writing equivalent of a clown suit. This does not wear well. Humor needs to come in under cover of darkness, in disguise, and surprise people. You don’t want to get that gdoing, gdoing, gdoing sound in your writing. It makes the reader feel sorry for you.

INTERVIEWER

Isn’t it possible that one of the problems with humor is that a lot of it is devoted to the topical, which then disappears so you no longer know quite what you should be laughing at?

KEILLOR

That’s true of stand-up comedy; it goes bad in about six months. But the problem for written humor is that nobody reads anymore. This makes humorists feel invisible, which is OK for poets, but humor is the only literary genre labeled by the effect it is supposed to have on people. So humor without an audience is pointless. No humorist has unpublished stuff. There is no great unpublished humor.

INTERVIEWER

I’m not so sure about that.

KEILLOR

No, no, take my word for it.

INTERVIEWER

Once you write it, it is noticed?

KEILLOR

Yes. It’s like sugar-beet farmers. You don’t hoard your crop. You put seeds in the ground, you get the crops out. But if people don’t read books, then we’ll have to switch over to soybeans.

INTERVIEWER

What should failed humorists do?

KEILLOR

Well, they should go into the ministry. Or they should write the sort of things that people want to read, which are profound essays about the future of our society that, though they are profound, nonetheless mention the names of celebrities.

INTERVIEWER

Have you tried this yourself?

KEILLOR

No, I haven’t.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever imagined seeing some of your stories filmed?

KEILLOR

I have. I went out to Los Angeles twice and talked to people about making Lake Wobegon into a film and discovered that film executives are much younger than I, and have never been to the Midwest. They’ve flown over it, but the movie was showing during that part of the trip. Nonetheless, these executives wanted to make a film with me, but . . . A midwesterner of my upbringing is a pessimist, so I began the meeting by saying that my work is full of problems and probably wouldn’t translate to the screen, and even if it did, people wouldn’t get it. This was a ritual of false modesty drilled into me as a child. I’m helpless to avoid it. I did it so well that I convinced them not to do it. When you grow up in a religious home, it makes a mark on you, and it’s not easy to get away from. They teach you, Don’t think you’re somebody, ’cause you’re not; you’re no different than anybody else. And I believe that, because it’s true.

INTERVIEWER

You spent some time abroad in Copenhagen. Did that change anything about your outlook or your habits or your view of things?

KEILLOR

You learn a great deal about yourself living in a foreign city, that’s for sure. When I had been there for a while, I started to meet some rural people whom you could really learn Danish from because that was the only language they knew. But at first, the only people I met were educated Copenhageners. You go to their homes for dinner, you see volumes of John Updike and Philip Roth and the Yale Shakespeare, and of course they speak perfect English, and it was hard to wrestle them out of English and into Danish so I could practice speaking my childlike, ungrammatical Danish. I’d wrestle them into Danish, and then they’d stay in Danish, and when they talked I couldn’t understand a word they said. I strove valiantly to be as Danish as possible so that when I walked into a bakery and said, Goddag, jeg vil gerne køb tre stykker, and the bakery girl looked at me and said, Oh you want three of those? it was a defeat. Danes don’t care about these exercises, they want to get it done, get it over with. I discovered, speaking Danish, that it was warping me, because the only Danish I knew was about food and love and beauty, and it was cheerful, bright, the language of complimenting people on the food and, Thank you for last time, and, Thank you for the herring, it was delicious. It was like living in a YMCA of the mind. I never found a way in Danish to express my meanness or make cutting remarks. All of my weapons were taken away from me.

INTERVIEWER

Why were you doing this in the first place?

KEILLOR

Because I was in their country, and I thought I should do the right thing and learn their language. But I couldn’t. I could only be a six-foot-three, two-hundred-pound four year old.

INTERVIEWER

So you came back.

KEILLOR

Yes. There’s not much future in being that large a child. But I had a wonderful time, and I am happy every time I go back. I talk my head off in Danish for about half an hour, until it’s used up, and then we speak English.

INTERVIEWER

I have forgotten the quintessential Paris Review question: what tools do you use when you write?

KEILLOR

I use a laptop computer. There are dangers in using a computer to write; it’s a fluid tool and you lose some of the concentration that a percussive tool like the typewriter gives you. But I’m tired of retyping the third draft. It’s too easy to write on a computer, the writing flows on and on like hot chocolate. So you have to print it out every so often and deal with it as a typescript, mark it up with pencil. As a final check, you force yourself to read it out loud. That is, I think, the surest detector of—I’m trying to think of a term other than horseshit, but I can’t—the clearest horseshit detector is to read it out loud. You can always tell when you’re putting on airs or lying when you hear yourself say it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think it’s important to make a point in writing humor?

KEILLOR

Yes. Humor has to take up absolutely everything in your life and deal with it. Humor is not about airline luggage or foreign taxicab drivers. It’s about our lives in America today, the ends of our lives, and everything that happened before and after. Why make jokes about food blenders or TV or the perils of dating after the age of thirty? It’s not an interesting way to spend your life. You’d much rather write pornography, and it would be better for everybody. When I am funny, I hope to be funny about Republicans, not about Pakistani taxi drivers.

INTERVIEWER

Which do you prefer, performing or writing?

KEILLOR

Well, that’s a good question. I keep on doing both performing and writing until I figure out the answer. But the only performing I do is of my own writing. So they’re almost the same thing.

INTERVIEWER

When did you actually decide to become a writer? And why?

KEILLOR

Well, it was surprising because I didn’t know anyone who was a writer. I grew up in a fundamentalist Protestant family that stressed very strongly one’s separation from the world, that we were a select people, selected by God to receive the revelation of his truth through the word and that we should conform not to this world, but renew our minds constantly through the faith. We were to avoid contact with others who did not share our faith. We were isolated, I think, just as much as the Hasidim or other religious minorities. Growing up in this world you got as a birthright a reverence for the word and for language. God spoke to us through the word. God did not give us pictures or ideograms, or speak to us through nature. God spoke to us through the word and in our family this was the King James Bible, which was an everyday part of our lives. Such a childhood gave fiction great power because it was proscribed. We were not to touch it. My family was shocked when I came home with a volume of Hemingway when I was boy. There was a price to be paid for being interested in fiction and in writing, you lost your family. I went to the University of Minnesota and fell in with writers, and after that writing was all I thought about. It’s a decision that always seems temporary and troubled, you’re never quite sure. Someone once asked John Berryman, How do you know if something you’ve written is good? And John Berryman said, You don’t. You never know, and if you need to know then you don’t want to be a writer. It’s a choice one makes that has constantly to be renewed. I’m only fifty-two, so I made a sort of a tentative choice that has lasted this long, but I could still fall back on radio. Or retail sales.

Courtesy: The Paris Review

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.