Thief’s charity is robber’s gain

(Satyapal Anand)

Today I did two things against the very grain of my nature. I normally do not give alms to beggars for I know it encourages them to earn by begging alone thus avoiding work. I gave a five dollar bill to an old man in rags waiting with “Some spare change, Sir?” on the side of steps going down to the Metro station. This was the first thing I did against my nature.

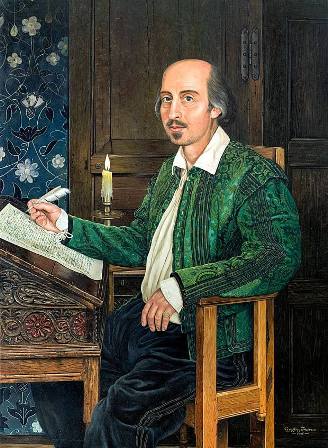

Why did I do it? I indeed knew. I had found a 10-dollar bill in a coat pocket that I had not worn for a year or two. When I put it on, it was a pleasant surprise to find this money in an inside pocket. I was beyond myself with joy. Was I the robber? Did I rob myself? How did I come across this 10-dollar bill originally? I didn’t remember but what I did remember was a quote from Shakespeare’s Othello. . Here it is.

The robbed that smiles steals something from the thief

Well, I smiled on recalling this line from the Bard of Avon. Was my smile the robber’s or the thief’s, I did not know, but what I did know was there was a sense of satisfaction after I had done this deed.

The second thing I did was to ask for the pardon of an old friend, who I knew was really good at heart but rather quick and caustic in sudden turns of his disposition. After I had done that I felt as if I had cleansed the bitterness from my mind.

This set me to thinking. Is there a way that can help me practice integrating service into my life? Well, so often, either consciously or unconsciously, we want something from others, especially when we have done something for them.

In my case I would think of having written a laudatory review of a literary friend’s book or a long, eulogistic and panegyric write up in a news-paper article.

“Why shouldn’t he do the same for me?” I might ask myself. If he doesn’t, I will feel let down. A good turn for a good turn is the norm, I’d say, isn’t it? And yet, if there is a bad turn for a good turn, doesn’t one feel turned down? Well, one does. I feel very uncomfortable when a friend remembers my one mistake of omission but chooses not to remember many good turns of commission done for him. That he conveniently forgot all my good deeds for him, I should know, is something that should weigh on his conscience, not mine. So, finally I decide I would keep on doing my good turns for him even if he doesn’t bother to notice them or turns his face the other way when he meets me. I will send him my greetings on Eid or Diwali or his birthday or an award-winning by him. If he doesn’t bother to acknowledge, so what! At least my own mind will be clean as a virgin slate.

Giving, or doing a good deed, I believe, should be a reward in itself. There’s a beautiful feeling of ease and peace after you’ve done it – and done with it, without waiting for a return. Just as vigorous exercise releases endorphins in our brain that make us feel good physically, so acts of loving kindness release the emotional equivalent of these endorphins. Our reward is the feeling we get in knowing that we participated in an act of kindness. We should not expect something in return or even a “thank you”.

In fact, we don’t even need the person know what we have done for him. Now, we are all human beings with our needs and some-times we do feel others could help in fulfilling these needs.

Therefore, what interferes with this peaceful feeling is our expectation of reciprocity. Our own thoughts interfere with our peaceful feelings as they clutter our minds, as we get caught up in what we think we want or need. The solution is to notice our “I want something in return” thoughts and gently dismiss them. In the absence of these thoughts, our positive feelings will return.

Please have a look also at: A torturer’s confessions

More from the same writer: اس نظم کی شان نزول

I believe when we have done something worthwhile for some-one without expecting anything in return, we build up, in the deepest recesses of our ‘self’, a storehouse of warm feelings which is always there for us to draw upon at times of misfortune. Isn’t this a reward in itself?

T.S. Eliot, in Murder in Cathedral, places this dialogue on the tongues of his characters:

Endurance of friendship does not depend

Upon ourselves, but upon circumstances

But circumstance is not undetermined.

Finally, I would give myself the benefit of two quotes that tell me never to bargain for a new friend in place of an old trusted one. Both these quotes are from Apocrypha

Ecclesiasticus, 9:10.

The first one is: “Forsake not an old friend for a new one does not compare with him.” The second one is:” A new friend is like new wine; when it has aged you will drink it with pleasure. In the meantime don’t throw away your old wine.”

If I conclude this piece with what Shakespeare had said, would that mean that the two friends mutually dealing with each other are just a thief and a robber or one who is selling fake goods، while the buyer is paying him in false coin۔

Well, both are happy. So what is the problem?

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.