Reviewing The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed

Prof. Himadri Banerjee

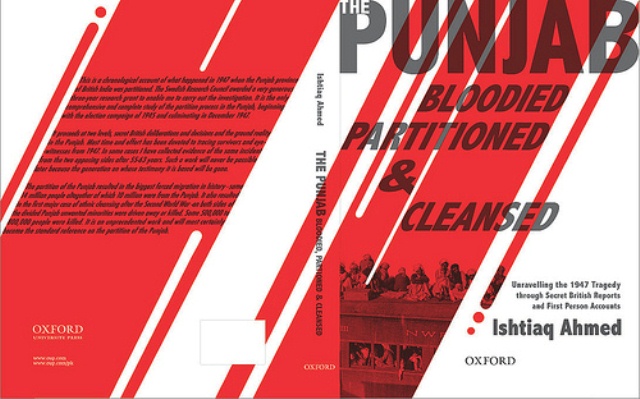

Ishtiaq Ahmed, The Punjab Bloodied Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First Person Accounts, New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2011, pp. 754, Rs. 995/-

Ishtiaq Ahmed’s pioneering study on Punjab Partition represents his nearly two decade long engagement with the subject.The author critically weaves together a vast mass of archival material which mainly evolves round the complex developments of high politics and their implications in different spheres of colonial administrative apparatus and beyond.

Nowadays, these documents are mostly available in the bulky volumes of Transfer of Power, four volume of the Governor’s Fortnightly Reports on the Punjab politics and other related official reports published by the successor nation-states and governmental bodies of the subcontinent.

The author makes no secret of his bigger interest in listening to the muted voices of hundreds of individuals who had directly or indirectly contributed or fell victim to the bloody process of Partition, intimately linked with the division of the province (1947). His numerous journeys in search of these oral sources carried him to distant countries beyond the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent and brought him into dialogue with cross sections of emigrant populations.

The process of recording their ‘traumatic experiences’ was conducted through interviews and they

were ‘allowed to narrate their story’ without interruptions. Its beginning was made in 1992. As he located new names, the numbers of interviewees significantly increased over the years. Incorporation of these materials has made the volume a significant contribution in the field of Partition historiography.

The scholar regards the Partition of Punjab essentially as an expression of ‘ethnic cleansing’ which sought ‘to eradicate unwanted people from their territory- the Muslim League against the Hindus and Sikhs from a united or divided Punjab, and the Sikhs against the Muslims from East Punjab.’

Ahmed agrees with Naimark that such large-scale cleansing was ‘not possible without state functionaries exploiting their power and authority to rid the country of people considered alien and unwanted because of their race, religion, sect, or language’ (2001). He finds that similar forms of ‘irrationality and aggression’ had earlier led to genocide of Jewish populations in Nazi Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe during Second World War as well as the dismantling of political unity of Yugoslavia and the limitless violence on the Albanians in Kosovo in the late twentieth century.

The division of British ruled colonial Punjab recreated many such experiences which led to the crossing of borders of around ‘nine to ten million’ Punjabis who had long lived as intimate neighbours and carried dialogue on wide-ranging issues, cutting across religious boundaries.

In spite of the frequency of bloody encounters occurring in different parts of the Punjab from March 1947 (following the resignation of the Khizr ministry) to the end of that year, the author doubts whether the partition of India formed a ‘sufficient basis for the partition of Punjab.’ He is critical of involvement of some front-ranking personalities of all three communities for abetting the crisis.

The announcement of the Radcliffe Award demarcating territorial boundaries between India and Pakistan at ‘the most inappropriate time’ made matters worse. It turned millions of people on the ‘wrong side of the line’ who were ‘easily targeted’ by their enemies and the colonial rulers were hardly ready to defend their life and property. Thus slaughter of innocent people accompanied by varied forms of violence relentlessly followed during these ten months in the year 1947. It was ‘a war of communities against other communities’ which gathered momentum by the desire to loot and plunder.

In the opinion of the author, it recreated Hobbes’s State of Nature when the colonial rule was receding and the new successor states of the subcontinent were grappling with manifold problems arising out of the largest human displacement and their uncertain journeys in search of new homes, leaving behind their native place.

The author, swayed by the human tragedies of these millions, has made them the subjects of his narrative. This makes his study valuable since the voices of the displaced were silenced at the birth of the two nations emerging out of their long colonial moorings.

The study has certain other distinguishing features. It not only differs from the findings of historians like Ian Talbot and Gurharpal Singh who earlier portrayed the British as ‘reluctant partitionists’ (2009) but also refuses to agree to the view of Mahajan (2000) that the Partition (1947) had taken place because the Congress was ‘forced to agree to the Muslim League’s political intransigence’.

Ahmed comes closer to the study of Gilmartin (1988) who concluded that it would be unfair to portray the Partition of the Punjab and the birth of Pakistan as neither dictated by the separatist politics of the Muslim League, nor intermittently fanned by the Divide and Rule stratagem long pursued by the British in the subcontinent.

The process had a deep emotional appeal which stimulated the rallying of the Muslims of Punjab under the banner of the Muslim League. The election results of January 1946 underlined the point. Its message of hope of providing the Muslims with a separate homeland in their native place served as a battle cry and became a strategy of community mobilisation in different western Punjab districts. This did not fail to reinforce links between urban middle classes and religious leaders with their extensive rural network scattered across the province.

Their alliance inspired cross-sections of Punjabi Muslims and gave the Muslim League a clear verdict in favour of their struggle for partitioning Punjab.

Ahmad’s major contribution, however, lies beyond the election verdict of 1946, but in its aftermath. His painstaking research in search of narratives of hundreds of those who were either active in different massacres of 1947 or had emerged as their victims has rendered the study with a grim and sombre dignity; these marginal voices of hundreds of protagonists of this mega-tragedy have not been deliberately homogenised, nor are these available in archival sources, nor are they marked by the ‘signs of gender’ which Butalia, Menon and Bhasin have already attempted to unearth in their respective Partition Studies.

There is yet another side to the story. Ahmed holds that ‘almost all those people who volunteered to talk’ spoke with great honesty’ and therefore, should be trusted since archival sources are unavailable to reconstruct this past of this. He claims to be standing on sure footing since he could detect the moments when some of them ‘were lying or distorting’ or making ‘new claims’ about their past.

One wonders, of course, how much has been lost in translation or rehearsed over time as the past became a distant object in subjective memory. Finally, in the process of growing distance from the traumatic event, these memories could necesarily become partial, fractured and selective. When situations turn volatile and things move faster than usual,

over which people have inadequate or little control, it is likely that the oral material could be seen as the intrusion of after-thoughts. It would largely depend upon a historian’s skill to bring together these scattered memories which the informants had looked back to recollect and referred to as experiences of violence and journeys of displaced persons in search of new destinations far away from their old home-steads.

In the absence of alternative material for constructing the history of these tumultuous months, Ahmed has done a superlative job with rare dedication and unique courage. This is a feat which a committed historian may aspire for but not necessarily achieve.

Himadri Banerjee, Former Guru Nanak Professor of Indian History, Jadavpur University, Kolkata

Editor’s note: This review was originally published in a quality academic journal, the Journal of History vol 31 (2016-17) and we arranged for aikRozan through the good offices of Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed. Moreover, this classic Partition Studies book under review has also been published by the Oxford University Press, OUP, Pakistan.